import pandas as pd # data manipulation and analysis.

import geopandas as gpd # spatial data operations

from shapely.geometry import Point, Polygon # handling geometric points

import numpy as np # multi-dimensional arrays and matrices

# Creating static, animated, and interactive visualizations in Python.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.colors import LinearSegmentedColormap

from matplotlib import cm

import seaborn as sns # drawing attractive statistical graphics.

# Adding basemaps

import contextily as cx # adding basemaps

# sklearn.cluster - a module in the Scikit-Learn library (sklearn) used for clustering (unsupervised learning)

from sklearn import metrics

from sklearn.cluster import DBSCAN

from sklearn.neighbors import NearestNeighbors

#ESDA: Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis

from esda.adbscan import ADBSCAN, get_cluster_boundary, remap_lblsLab in Python

Points

Points are spatial entities that can be understood in two fundamentally different ways. On the one hand, points can be seen as fixed objects in space, which is to say their location is taken as given (exogenous). In this case, analysis of points is very similar to that of other types of spatial data such as polygons and lines. On the other hand, points can be seen as the occurence of an event that could theoretically take place anywhere but only manifests in certain locations. This is the approach we will adopt in the rest of the notebook.

When points are seen as events that could take place in several locations but only happen in a few of them, a collection of such events is called a point pattern. In this case, the location of points is one of the key aspects of interest for analysis. A good example of a point pattern is crime events in a city: they could technically happen in many locations but we usually find crimes are committed only in a handful of them. Point patterns can be marked, if more attributes are provided with the location, or unmarked, if only the coordinates of where the event occured are provided. Continuing the crime example, an unmarked pattern would result if only the location where crimes were committed was used for analysis, while we would be speaking of a marked point pattern if other attributes, such as the type of crime, the extent of the damage, etc. was provided with the location.

Point pattern analysis is thus concerned with the description, statistical characerisation, and modeling of point patterns, focusing specially on the generating process that gives rise and explains the observed data. What’s the nature of the distribution of points? Is there any structure we can statistically discern in the way locations are arranged over space? Why do events occur in those places and not in others? These are all questions that point pattern analysis is concerned with.

This notebook aims to be a gentle introduction to working with point patterns in Python. As such, it covers how to read, process and transform point data, as well as several common ways to visualize point patterns.

Importing Modules

Data

We are going to continue with Airbnb data in a different part of the world.

Airbnb Buenos Aires

Let’s read in the point dataset:

# read the Airbnb listing

listings = pd.read_csv("data/BuenosAires/listings_nooutliers.csv")

# Show summary statistics of the dataset

print(listings.describe()) id host_id neighbourhood_group latitude \

count 1.857200e+04 1.857200e+04 0.0 18572.000000

mean 2.867385e+07 1.086210e+08 NaN -34.592447

std 1.418299e+07 1.075071e+08 NaN 0.017905

min 6.283000e+03 2.616000e+03 NaN -34.689621

25% 1.846015e+07 1.383494e+07 NaN -34.602909

50% 3.175833e+07 6.603382e+07 NaN -34.591709

75% 4.000713e+07 1.889644e+08 NaN -34.582119

max 5.110064e+07 4.125068e+08 NaN -34.533298

longitude price minimum_nights number_of_reviews

count 18572.000000 18572.000000 18572.000000 18572.000000

mean -58.415045 5423.835667 6.996016 15.924779

std 0.029366 28865.078495 20.730803 33.354753

min -58.530930 218.000000 1.000000 0.000000

25% -58.434413 1800.000000 2.000000 0.000000

50% -58.414255 2790.000000 3.000000 3.000000

75% -58.391129 4470.500000 5.000000 16.000000

max -58.355412 962109.000000 730.000000 500.000000 Let’s finish preparing it, note the CRS.

# Locate the longitude and latitude

print(listings.columns)

# Use columns 'longitude' and 'latitude' respectively

listings_gdf = gpd.GeoDataFrame(

listings, geometry=gpd.points_from_xy(listings.longitude, listings.latitude), crs="EPSG:4326"

)Index(['id', 'name', 'host_id', 'host_name', 'neighbourhood_group',

'neighbourhood', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'room_type', 'price',

'minimum_nights', 'number_of_reviews', 'last_review'],

dtype='object')Adminstrative Areas

We will later use administrative areas for aggregation. Let’s load them.

# We will later use administrative areas for aggregation. Let's load them.

BA = gpd.read_file("data/BuenosAires/neighbourhoods_BA.shp")Spatial Join

# Perform spatial overlay between points and polygons

listings_BA = listings_gdf.sjoin(BA, how="inner", predicate='intersects')

# Read the first lines of the attribute table

print(listings_BA.head()) id name host_id host_name \

0 6283 Casa Al Sur 13310 Pamela

11 15889 ROOM W /BALCONY-DOWNTOWN ...... 62183 Sonia

105 93174 B&B "Tucuman 2430"1 room x 1 or 2p 500210 Luciano

116 107259 Great place to 12 Tango lovers 555693 Vittoria

123 119966 Room with library downtown 62183 Sonia

neighbourhood_group neighbourhood latitude longitude room_type \

0 NaN Balvanera -34.605228 -58.410419 Entire home/apt

11 NaN Balvanera -34.603458 -58.411789 Private room

105 NaN Balvanera -34.602989 -58.401939 Private room

116 NaN Balvanera -34.605141 -58.395699 Entire home/apt

123 NaN Balvanera -34.603958 -58.400681 Private room

price minimum_nights number_of_reviews last_review \

0 4810 3 1 2011-01-31

11 3505 3 6 2011-07-11

105 1136 2 10 2012-08-04

116 38384 3 26 2018-02-12

123 3506 3 0 NaN

geometry index_right neighbourh neighbou_1

0 POINT (-58.41042 -34.60523) 30 Balvanera NaN

11 POINT (-58.41179 -34.60346) 30 Balvanera NaN

105 POINT (-58.40194 -34.60299) 30 Balvanera NaN

116 POINT (-58.39570 -34.60514) 30 Balvanera NaN

123 POINT (-58.40068 -34.60396) 30 Balvanera NaN .sjoin(BA, how="inner", predicate='intersects'): This function performs a spatial join between listings_gdf and BA where:how="inner"ensures that only matching records (where the spatial relationship is true) are included.predicate='intersects'specifies that the join condition is based on whether the geometries intersect.

One-to-one

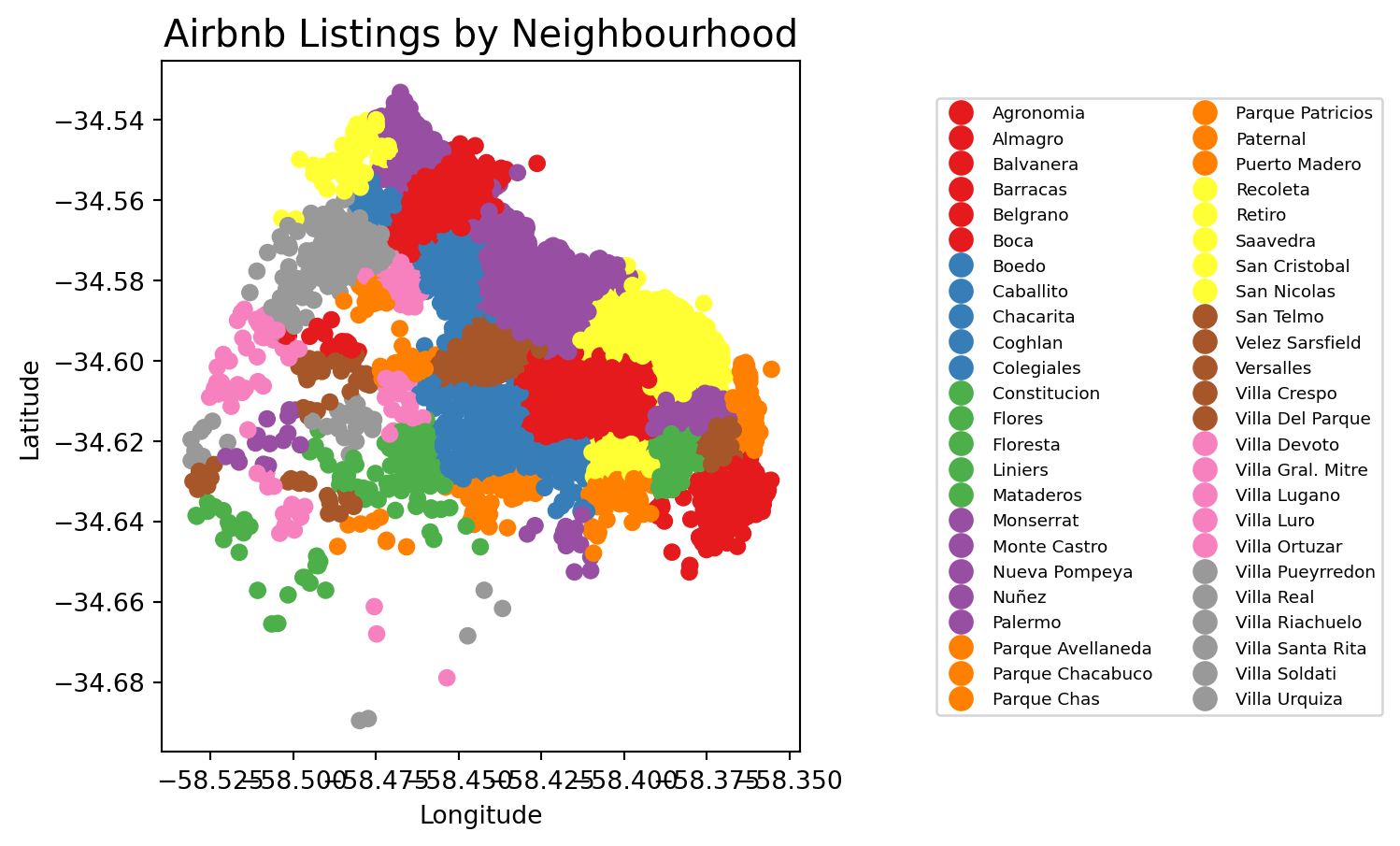

The first approach we review here is the one-to-one approach, where we place a dot on the screen for every point to visualise. In order to actually see all the neighbourhood names we need to do a bit of formatting work.

# Assuming 'neighbourhood' is a column in your listings_gdf GeoDataFrame

# Plot the GeoDataFrame with neighborhoods colored differently

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(15, 5))

listings_gdf.plot(column='neighbourhood', ax=ax, legend=True, cmap='Set1',

legend_kwds={'loc': 'center left', 'bbox_to_anchor': (1.2, 0.5), 'fontsize': 'x-small', 'ncol': 2, "fmt": "{:.0f}"})

# Set plot title and labels

ax.set_title('Airbnb Listings by Neighbourhood', fontsize=15)

ax.set_xlabel('Longitude')

ax.set_ylabel('Latitude')

# Adjust the subplot parameters to give more space for the legend

plt.subplots_adjust(right=0.5)

# Show the plot

plt.show()

figsize=(35, 10): create different spaces for map and legend part of imagelegend_kwds: This dictionary allows you to customize the legend’s position and appearance.loc='center left': Positions the legend on the center left of the bounding box.bbox_to_anchor=(1.2, 0.5): Moves the legend outside the plot area to the right. The (1.2, 0.5) specifies that the anchor point of the legend is placed at 120% (right edge) on the x-axis and 50% (center) on the y-axis of the bounding box.fontsize='x-small': This reduces the size of the text in the legend. You can use specific sizes like ‘small’, ‘x-small’, ‘medium’, or specify a numeric value (e.g., fontsize=8).'ncol': 2: This specifies that the legend should be displayed in two columns. You can adjust this number to display more or fewer columns as needed.

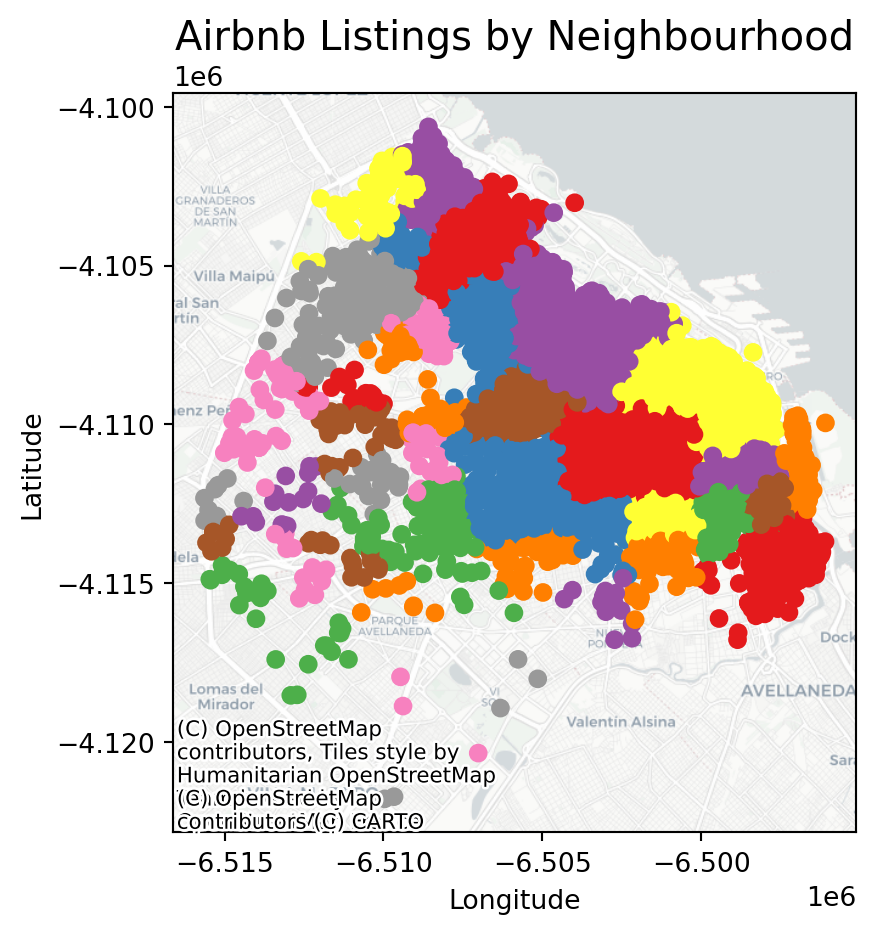

We can visualise a bit better with a basemap

# If it's not already, convert it using `to_crs(epsg=3857)`

listings_gdf_3857 = listings_gdf.to_crs(epsg=3857)

# Assuming `listings_gdf` is your GeoDataFrame and it's already loaded with data

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(15, 5))

# Plot the GeoDataFrame

listings_gdf_3857.plot(column='neighbourhood', ax=ax, legend=False, cmap='Set1')

# Add basemap using contextily

# Note: The GeoDataFrame needs to be in Web Mercator projection for contextily basemaps

#listings_gdf = listings_gdf.to_crs(epsg=3857)

#cx.add_basemap(ax, crs=listings_gdf_3857.crs.to_string())

cx.add_basemap(

ax,

crs="EPSG:3857",

source=cx.providers.CartoDB.Positron

)

# Set plot title and labels

ax.set_title('Airbnb Listings by Neighbourhood', fontsize=15)

ax.set_xlabel('Longitude')

ax.set_ylabel('Latitude')

# Show the plot

plt.show()

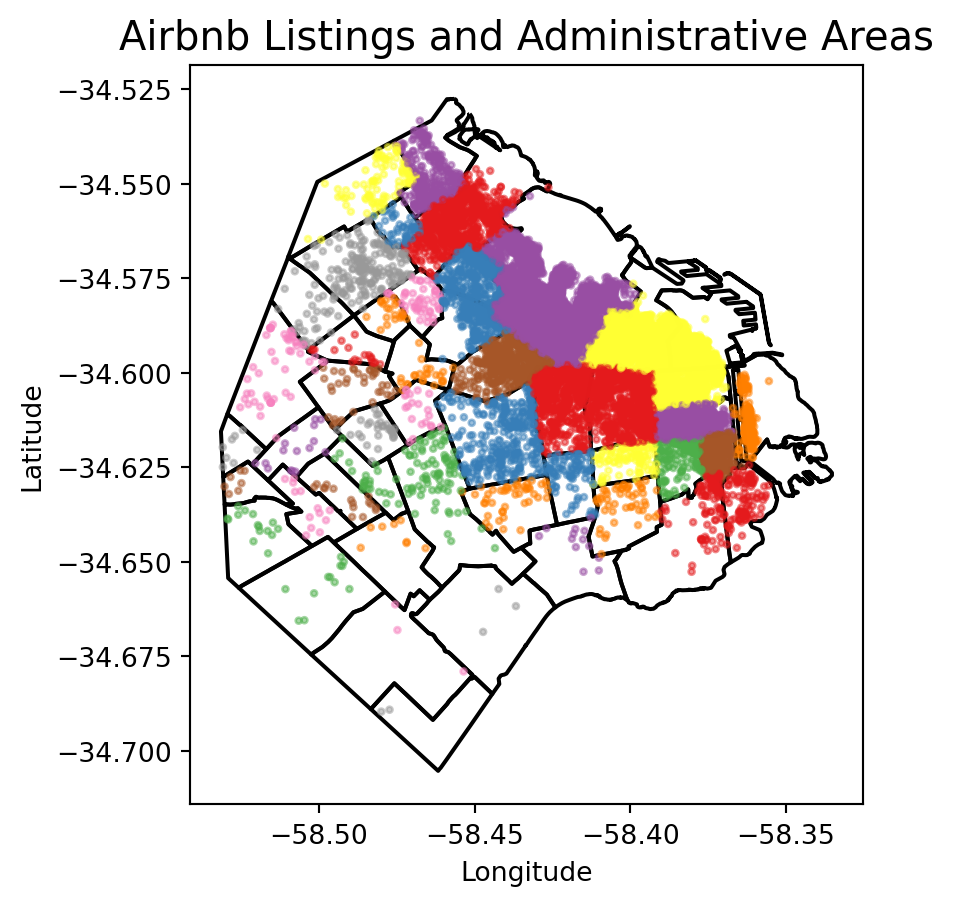

Points meet polygons

The approach presented above works until a certain number of points to plot; tweaking dot transparency and size only gets us so far and, at some point, we need to shift the focus. Having learned about visualizing lattice (polygon) data, an option is to “turn” points into polygons and apply techniques like choropleth mapping to visualize their spatial distribution. To do that, we will overlay a polygon layer on top of the point pattern, join the points to the polygons by assigning to each point the polygon where they fall into, and create a choropleth of the counts by polygon.

This approach is intuitive but of course raises the following question: what polygons do we use to aggregate the points? Ideally, we want a boundary delineation that matches as closely as possible the point generating process and partitions the space into areas with a similar internal intensity of points. However, that is usually not the case, no less because one of the main reasons we typically want to visualize the point pattern is to learn about such generating process, so we would typically not know a priori whether a set of polygons match it. If we cannot count on the ideal set of polygons to begin with, we can adopt two more realistic approaches: using a set of pre-existing irregular areas or create a artificial set of regular polygons. Let’s explore both.

Irregular lattices

To exemplify this approach, we will use the administrative areas we have loaded above. Let’s add them to the figure above to get better context (unfold the code if you are interested in seeing exactly how we do this):

# Plot the administrative boundaries (BA) and listings with neighborhoods colored differently

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5, 5))

# Plot the BA GeoDataFrame with no fill and a specific line size

BA.plot(ax=ax, edgecolor='black', linewidth=1.5, facecolor='none')

# Plot the listings with neighborhoods colored differently, specific point size, and transparency

listings_gdf.plot(column='neighbourhood', ax=ax, cmap='Set1', markersize=5, alpha=0.5)

# Set plot title and labels

ax.set_title('Airbnb Listings and Administrative Areas', fontsize=15)

ax.set_xlabel('Longitude')

ax.set_ylabel('Latitude')

# Show the plot

plt.show()

Now we need to know how many airbnb each area contains.

# Aggregate at district level

listings_BA_agg = listings_BA.groupby(['neighbourh']).agg(

count_airbnb=('price', 'size'), # count number of sales

mean_price=('price', 'mean') # calculate average price

).reset_index()

# Merge the aggregated data back with the original GeoDataFrame to retain geometry

airbnb_neigh_agg = BA[['neighbourh', 'geometry']].drop_duplicates().merge(

listings_BA_agg, on='neighbourh'

)The lines above have created a new column in our table called count_airbnb that contains the number of airbnb that have been taken within each of the polygons in the table. mean_price shows the mean price per neighbourhood.

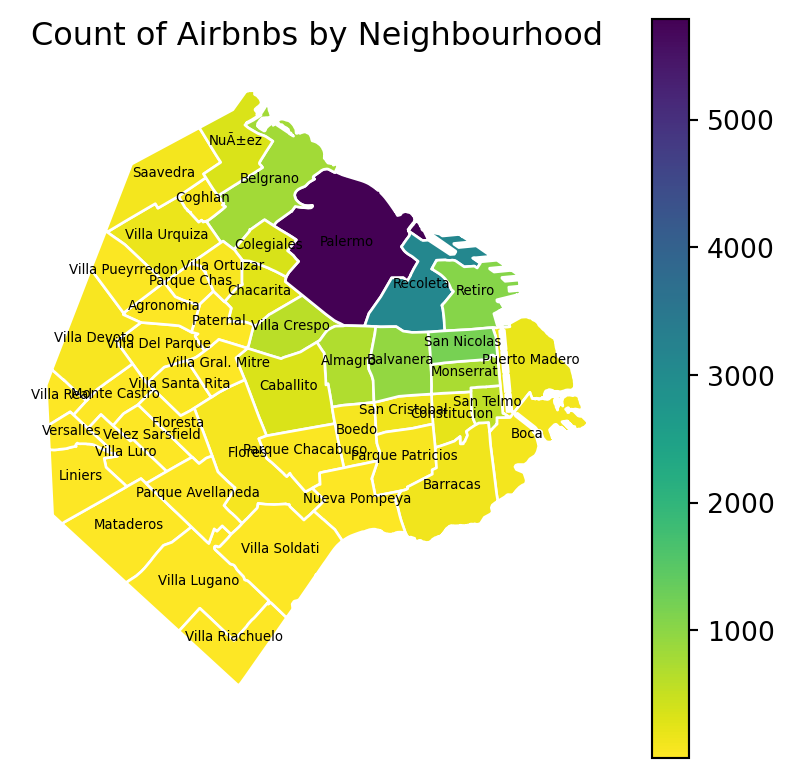

At this point, we are ready to map the counts. Technically speaking, this is a choropleth just as we have seen many times before:

# Create a figure and axis for plotting

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5, 5))

# Reverse the 'viridis' colormap

viridis = plt.get_cmap('viridis')

viridis_reversed = viridis.reversed()

# Plot the geometries with fill color based on 'count_airbnb' and a white border

airbnb_neigh_agg.plot(column='count_airbnb', ax=ax, edgecolor='white', cmap=viridis_reversed, legend=True)

# Add text labels at the centroids of the districts

for idx, row in airbnb_neigh_agg.iterrows():

centroid = row['geometry'].centroid

ax.text(centroid.x, centroid.y, row['neighbourh'], fontsize=5, ha='center')

# Set the title

ax.set_title("Count of Airbnbs by Neighbourhood")

# Remove axis

ax.set_axis_off()

# Show the plot

plt.show()

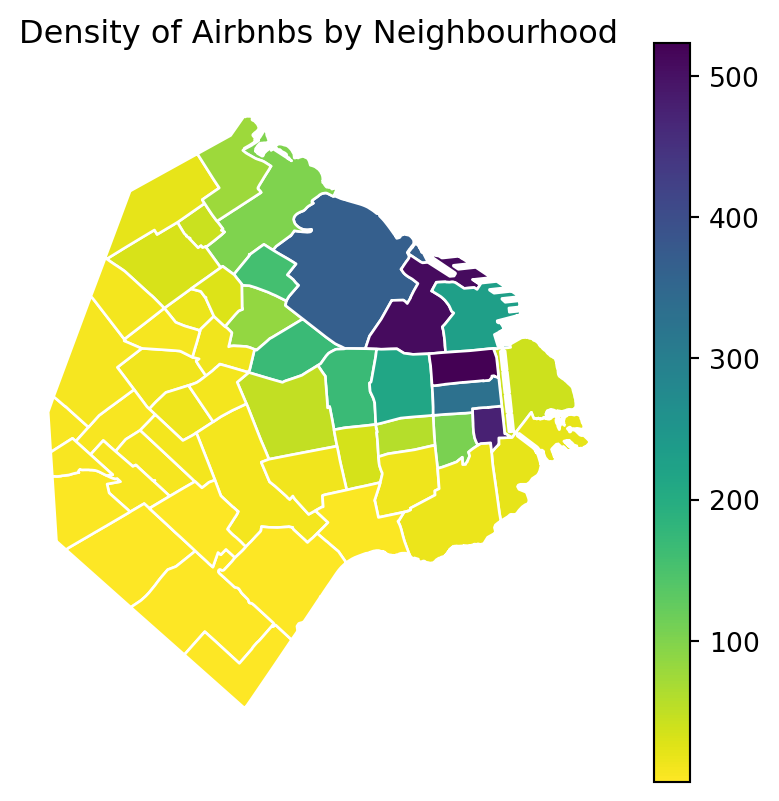

The map above clearly shows a concentration of airbnb in the neighbourhoods of Palermo and Recoleta. However, it is important to remember that the map is showing raw counts. In the case of airbnbs, as with many other phenomena, it is crucial to keep in mind the “container geography” (MAUP). In this case, different administrative areas have different sizes. Everything else equal, a larger polygon may contain more photos, simply because it covers a larger space. To obtain a more accurate picture of the intensity of photos by area, what we would like to see is a map of the density of photos, not of raw counts. To do this, we can divide the count per polygon by the area of the polygon.

Let’s first calculate the area in Sq. metres of each administrative delineation:

# Convert CRS to EPSG:22176 for Argentina

airbnb_neigh_agg_proj = airbnb_neigh_agg.to_crs(epsg=22176)

# Calculate area in square kilometers and add it to the DataFrame

airbnb_neigh_agg_proj['area_km2'] = airbnb_neigh_agg_proj.geometry.area / 1e6 # Convert area to square kilometers

# Calculate density

airbnb_neigh_agg_proj['density'] = airbnb_neigh_agg_proj['count_airbnb'] / airbnb_neigh_agg_proj['area_km2']With the density at hand, creating the new choropleth is similar as above:

# Create a figure and axis for plotting

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5, 5))

# Reverse the 'viridis' colormap

viridis = plt.get_cmap('viridis')

viridis_reversed = viridis.reversed()

# Plot the geometries with fill color based on 'count_airbnb' and a white border

airbnb_neigh_agg_proj.plot(column='density', ax=ax, edgecolor='white', cmap=viridis_reversed, legend=True)

# Set the title

ax.set_title("Density of Airbnbs by Neighbourhood")

# Remove axis

ax.set_axis_off()

# Show the plot

plt.show()

We can see some significant differences. Why is that? Have a chat with the person next to you.

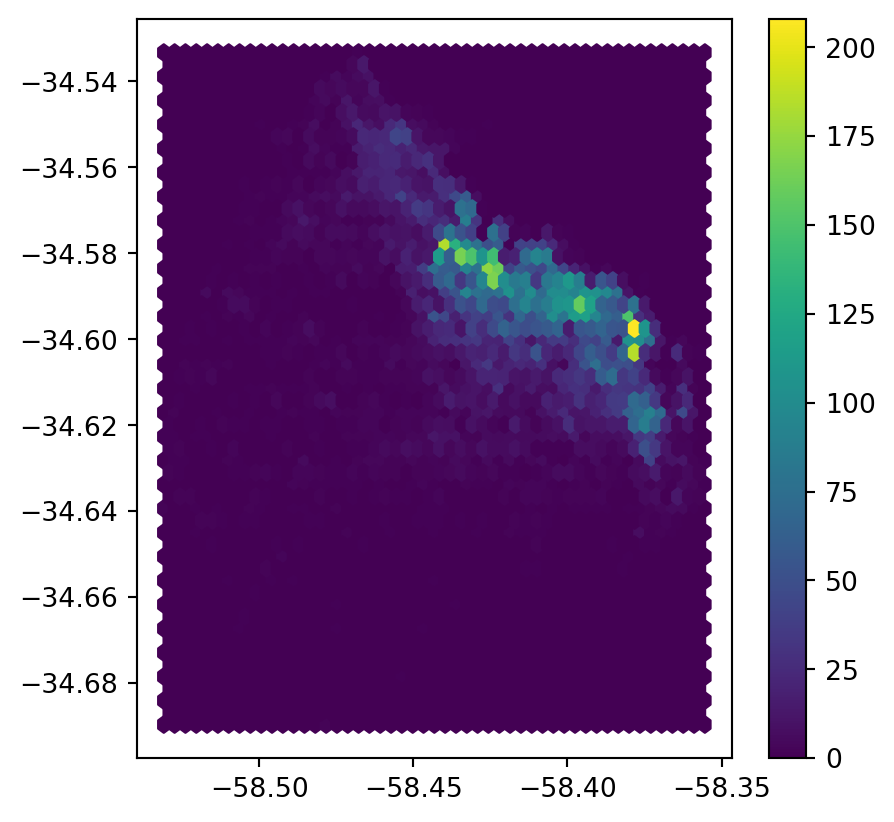

Regular lattices: hex-binning

Sometimes we either do not have any polygon layer to use or the ones we have are not particularly well suited to aggregate points into them. In these cases, a sensible alternative is to create an artificial topology of polygons that we can use to aggregate points. There are several ways to do this but the most common one is to create a grid of hexagons. This provides a regular topology (every polygon is of the same size and shape) that, unlike circles, cleanly exhausts all the space without overlaps and has more edges than squares, which alleviates edge problems.

If you are still still not sure on the difference between geographic coordinate systems and projected coordinated system go back to Lecture 1.

First we need to make sure we are in a projected coordinated system:

# Reproject the administrative areas to the CRS for Argentina (EPSG:22176)

BA_proj = BA.to_crs(epsg=22176)

# Reproject the listings to match the CRS of the administrative areas

listings_proj = listings_gdf.to_crs(epsg=22176)Then we create a grid that’s 500 metre by 500 metres. We need to be in a projected coordinate system for this to work.

Python has a simplified way to create this hexagon layer and aggregate points into it in one shot thanks to the method hexbin, which is available in every axis object (e.g. ax). Let us first see how you could create a map of the hexagon layer alone:

# Setup figure and axis

f, ax = plt.subplots(1, figsize=(5, 5))

# Add hexagon layer that displays count of points in each polygon

hb = ax.hexbin(

listings_proj["longitude"],

listings_proj["latitude"],

gridsize=50,

)

# Add a colorbar (optional)

plt.colorbar(hb)

# Show the plot

plt.show()

Let’s unpack the coded here:

- Call

hexbindirectly using the set of coordinate columnslistings_proj["longitude"]andlistings_proj["latitude"]. - Additional arguments we include is the number of hexagons by axis (gridsize, 50 for a 50 by 50 layer), and the transparency we want (80%).

- Additionally, we include a colorbar to get a sense of how counts are mapped to colors. Note that we need to pass the name of the object that includes the

hexbin(hb in our case), but keep in mind this is optional, you do not need to always create one.

You could also add a basemap to visualise the results better as we’ve done in other code snippets.

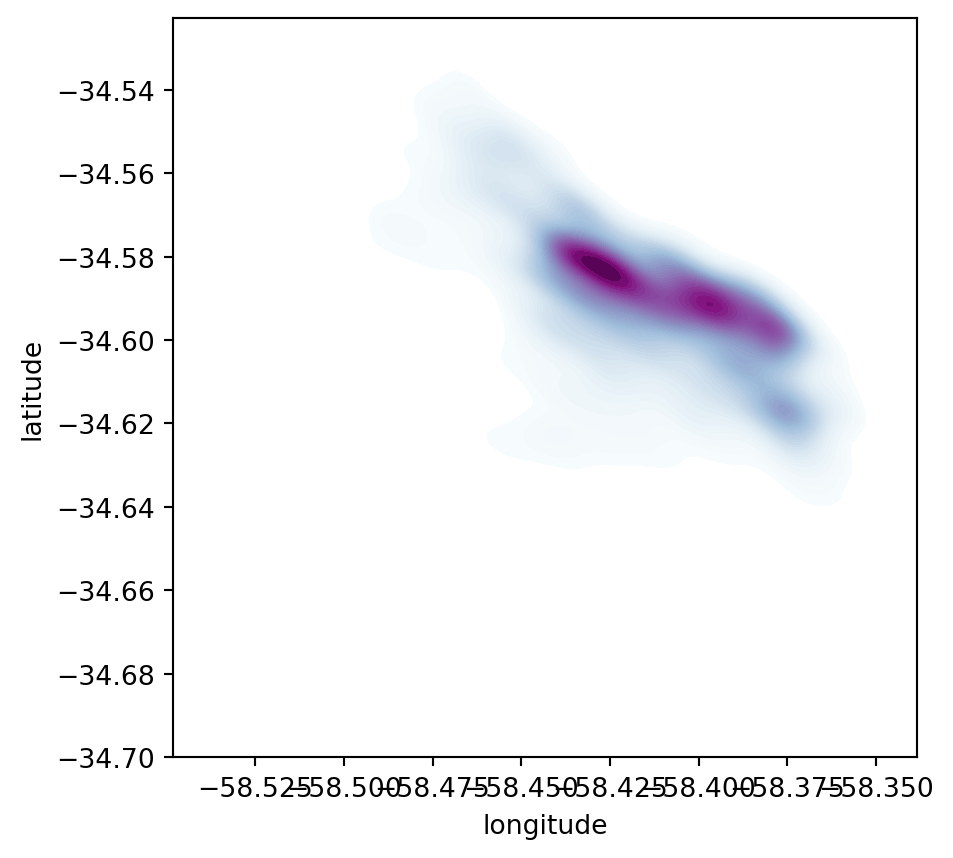

Kernel Density Estimation

Using a hexagonal binning can be a quick solution when we do not have a good polygon layer to overlay the points directly and some of its properties, such as the equal size of each polygon, can help alleviate some of the problems with a “bad” irregular topology (one that does not fit the underlying point generating process). However, it does not get around the issue of the modifiable areal unit problem M.A.U.P.: at the end of the day, we are still imposing arbitrary boundary lines and aggregating based on them, so the possibility of mismatch with the underlying distribution of the point pattern is very real.

One way to work around this problem is to avoid aggregating into another geography altogether. Instead, we can aim at estimating the continuous observed probability distribution. The most commonly used method to do this is the so called kernel density estimate (KDE). The idea behind KDEs is to count the number of points in a continious way. Instead of using discrete counting, where you include a point in the count if it is inside a certain boundary and ignore it otherwise, KDEs use functions (kernels) that include points but give different weights to each one depending of how far of the location where we are counting the point is.

Kernel densities

The actual algorithm to estimate a kernel density is not trivial but its application in Python is rather simplified by the use of seaborn. KDE’s however are fairly computationally intensive. When you have a large point pattern like we do in the Buenos Aires example (18,572 points), its computation can take a bit long. To get around this issue, you can create a random subset, which retains the overall structure of the pattern, but with much fewer points. Let’s take a subset of 1,000 random points from our original table:

# Take a random subset of 1,000 rows from `buenos aires listings`

listings_proj_sub = listings_proj.sample(1000, random_state=12345)- Note we need to specify the size of the resulting subset (1,000), and we also add a value for

random_state; this ensures that the sample is always the same and results are thus reproducible.

Same as above, let us first see how to create a quick KDE. For this we rely on seaborn’s kdeplot:

# Setup figure and axis

f, ax = plt.subplots(1, figsize=(5, 5))

# using kdeplot

sns.kdeplot(

x="longitude",

y="latitude",

data=listings_proj,

n_levels=50,

fill=True,

cmap='BuPu'

);

# Show the plot

plt.show()

Seaborngreatly streamlines the process and boils it down to a single line.- The method

sns.kdeplot(which we can also use to create a KDE of a single variable) takes the X and Y coordinate of the points as the only compulsory attributes. - In addition, we specify the number of levels we want the color gradient to have (

n_levels), whether we want to color the space in between each level (share, yes), and thecolormapof choice.

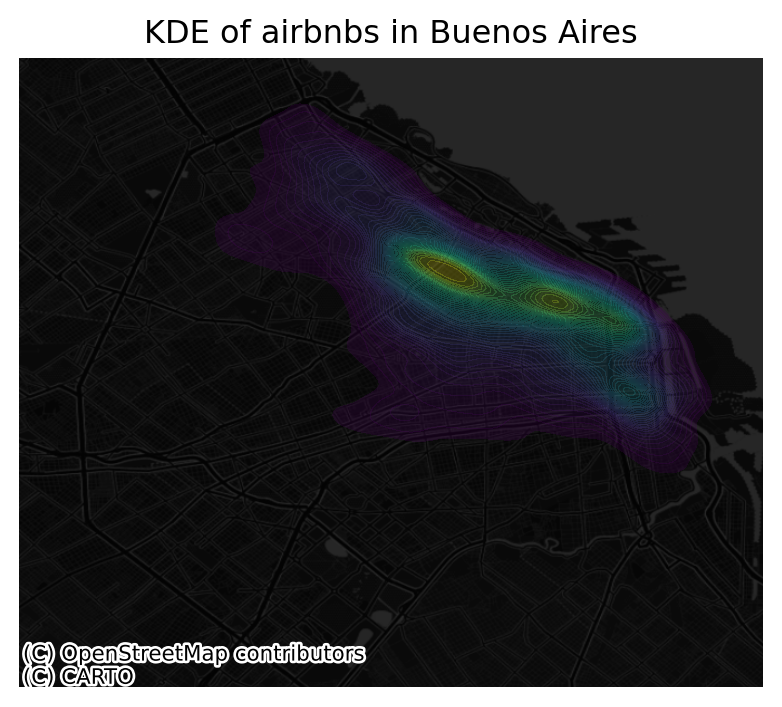

Once we know how the basic logic works, we can insert it into the usual mapping machinery to create a more complete plot. The main difference here is that we now have to tell sns.kdeplot where we want the surface to be added (ax in this case). Toggle the expandable to find out the code that produces the figure below:

# Setup figure and axis

f, ax = plt.subplots(1, figsize=(5, 5))

# Add KDE layer that displays probability surface

sns.kdeplot(

x='longitude',

y='latitude',

data=listings, # because it is in 4326

n_levels=50,

fill=True,

alpha=0.25,

cmap="viridis"

)

# Remove axis

ax.set_axis_off()

# Add basemap

cx.add_basemap(

ax,

crs="EPSG:4326",

source=cx.providers.CartoDB.DarkMatterNoLabels

)

# Add title of the map

ax.set_title("KDE of airbnbs in Buenos Aires")

# Draw map

plt.show()

Cluster of points (DBSCAN)

Partitioning methods (K-means, PAM clustering) and hierarchical clustering are suitable for finding spherical-shaped clusters or convex clusters. In other words, they work well for compact and well separated clusters. Moreover, they are also severely affected by the presence of noise and outliers in the data.

Unfortunately, real life data can contain: i) clusters of arbitrary shape ii) many outliers and noise.

In this section, we will learn a method to identify clusters of points, based on their density across space. To do this, we will use the widely used DBSCAN algorithm. For this method, a cluster is a concentration of at least m points, each of them within a distance of r of at least another point in the cluster. Points in the dataset are then divided into three categories:

- Noise, for those points outside a cluster.

- Cores, for those points inside a cluster whith at least

mpoints in the cluster within distancer. - Borders for points inside a cluster with less than

mother points in the cluster within distancer.

Both m and r need to be prespecified by the user before running DBSCAN. This is a critical point, as their value can influence significantly the final result. Before exploring this in greater depth, let us get a first run at computing DBSCAN in Python. For more on this, check here.

The DBSCAN approach

The heavy lifting is done by the method DBSCAN, part of the excellent machine learning library scikit-learn. We first set up the details:

eps: maximum distance to look for neighbors from each locationmin_samples: minimum number of neighboring points required for a point to be considered part of a cluster

# Set up algorithm

algo = DBSCAN(eps=100, min_samples=50)We decide to consider a cluster of airbnb with more than 50 airbnbs within 100 metres from them, hence we set the two parameters accordingly. Once ready, we “fit” it to our data, but note that we first need to express the longitude and latitude of our points in metres. We have already projected to the Argentinian CRS but let’s revise this.

## Express points in metres

# Convert lon/lat into Point objects + set CRS

pts = gpd.points_from_xy(

listings["longitude"],

listings["latitude"],

crs="EPSG:4326"

)

# Convert lon/lat points to Buenos Aires CRS in metres

pts = gpd.GeoDataFrame({"geometry": pts}).to_crs(epsg=22176)

# Extract coordinates from point objects into columns

listings["X_metres"] = pts.geometry.x

listings["Y_metres"] = pts.geometry.yalgo.fit(listings[["X_metres", "Y_metres"]])DBSCAN(eps=100, min_samples=50)In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

DBSCAN(eps=100, min_samples=50)

Once fit, we can recover the labels:

algo.labels_array([-1, 0, -1, ..., -1, -1, -1])And the list of points classified as cores:

# Print only the first five values

algo.core_sample_indices_[:5]array([ 1, 14, 24, 27, 52])The labels_ object always has the same length as the number of points used to run DBSCAN. Each value represents the index of the cluster a point belongs to. If the point is classified as noise, it receives a -1. Above, we can see that the first five points are effectively not part of any cluster. To make thinks easier later on, let us turn the labels into a Series object that we can index in the same way as our collection of points:

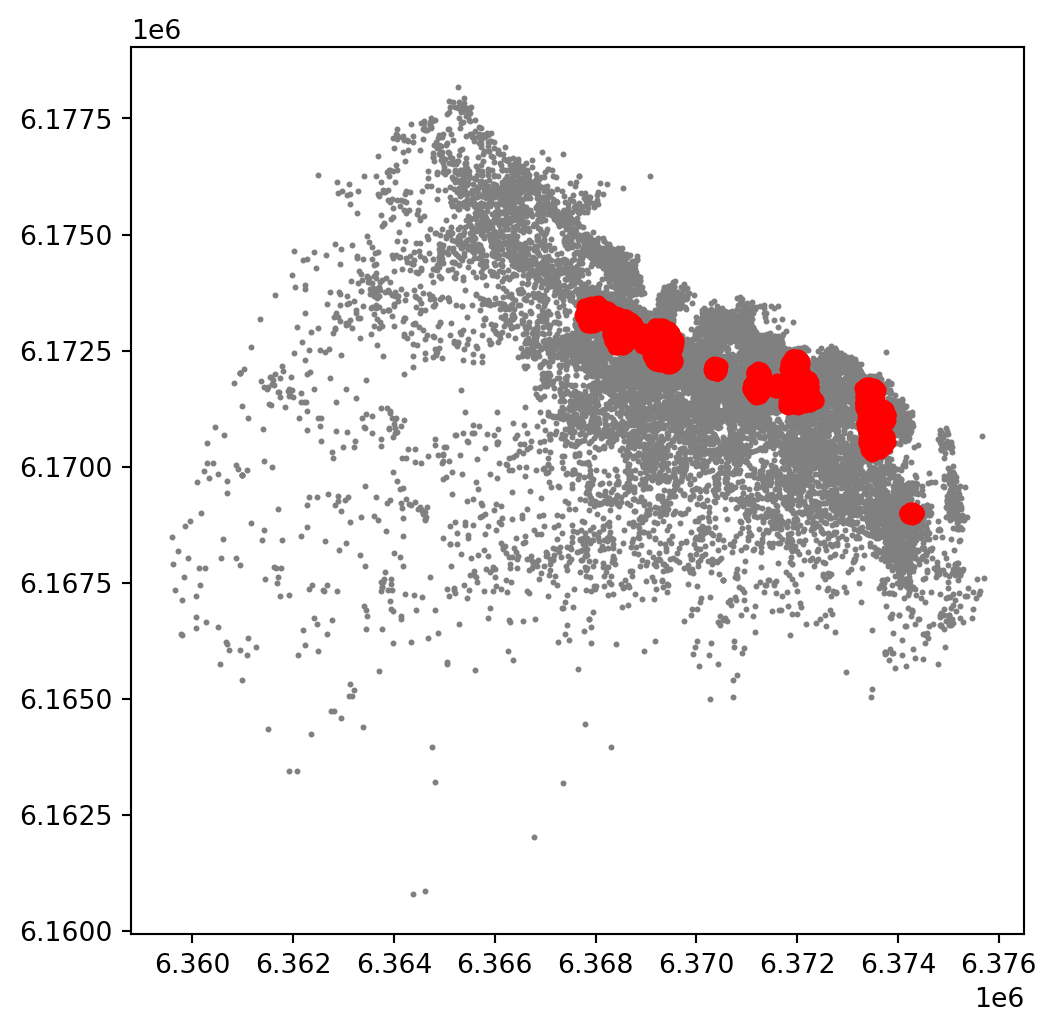

lbls = pd.Series(algo.labels_, index=listings.index)Now we already have the clusters, we can proceed to visualize them. There are many ways in which this can be done. We will start just by coloring points in a cluster in red and noise in grey:

# Setup figure and axis

f, ax = plt.subplots(1, figsize=(6, 6))

# Assign labels to tokyo table dynamically and

# subset points that are not part of any cluster (noise)

noise = listings.assign(

lbls=lbls

).query("lbls == -1")

# Plot noise in grey

ax.scatter(

noise["X_metres"],

noise["Y_metres"],

c='grey',

s=5,

linewidth=0

)

# Plot all points that are not noise in red

# NOTE how this is done through some fancy indexing, where

# we take the index of all points (tw) and substract from

# it the index of those that are noise

ax.scatter(

listings.loc[listings.index.difference(noise.index), "X_metres"],

listings.loc[listings.index.difference(noise.index), "Y_metres"],

c="red",

linewidth=0

)

# Display the figure

plt.show()

This is a first good pass. The algorithm is able to identify a few clusters with high density of airbnbs. However, as we mentioned when discussing DBSCAN, this is all contingent on the parameters we arbitrarily set. Depending on the maximum radious (eps) we set, we will pick one type of cluster or another: a higher (lower) radious will translate in less (more) local clusters. Equally, the minimum number of points required for a cluster (min_samples) will affect the implicit size of the cluster. Both parameters need to be set before running the algorithm, so our decision will affect the final outcome quite significantly.

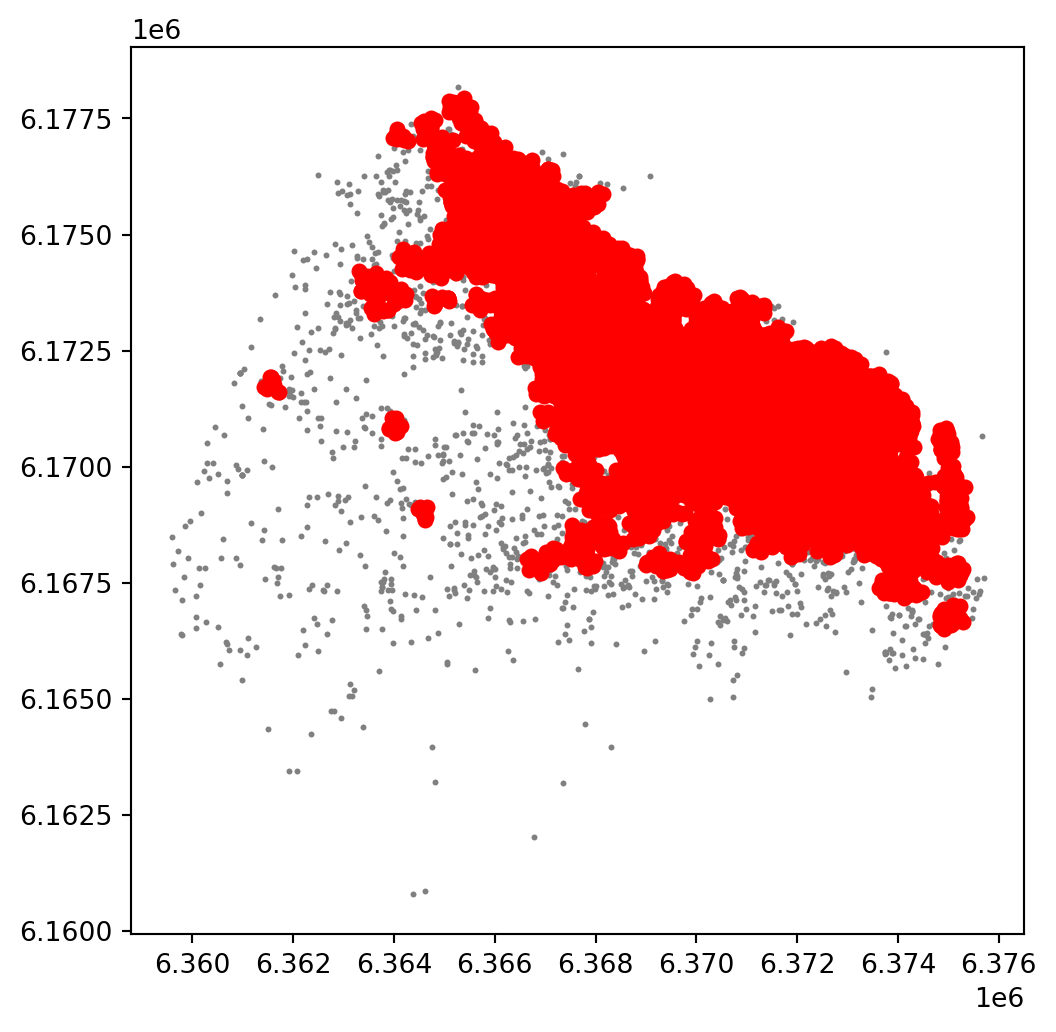

For an illustration of this, let’s run through a case with very different parameter values. For example, let’s pick a larger radious (e.g. 250m) and a smaller number of points (e.g. 10):

# Set up algorithm

algo = DBSCAN(eps=200, min_samples=10)

# Fit to Tokyo projected points

algo.fit(listings[["X_metres", "Y_metres"]])

# Store labels

lbls = pd.Series(algo.labels_, index=listings.index)And let’s now visualise the result (toggle the expandable to see the code):

# Setup figure and axis

f, ax = plt.subplots(1, figsize=(6, 6))

# Assign labels to tokyo table dynamically and

# subset points that are not part of any cluster (noise)

noise = listings.assign(

lbls=lbls

).query("lbls == -1")

# Plot noise in grey

ax.scatter(

noise["X_metres"],

noise["Y_metres"],

c='grey',

s=5,

linewidth=0

)

# Plot all points that are not noise in red

# NOTE how this is done through some fancy indexing, where

# we take the index of all points (tw) and substract from

# it the index of those that are noise

ax.scatter(

listings.loc[listings.index.difference(noise.index), "X_metres"],

listings.loc[listings.index.difference(noise.index), "Y_metres"],

c="red",

linewidth=0

)

# Display the figure

plt.show()

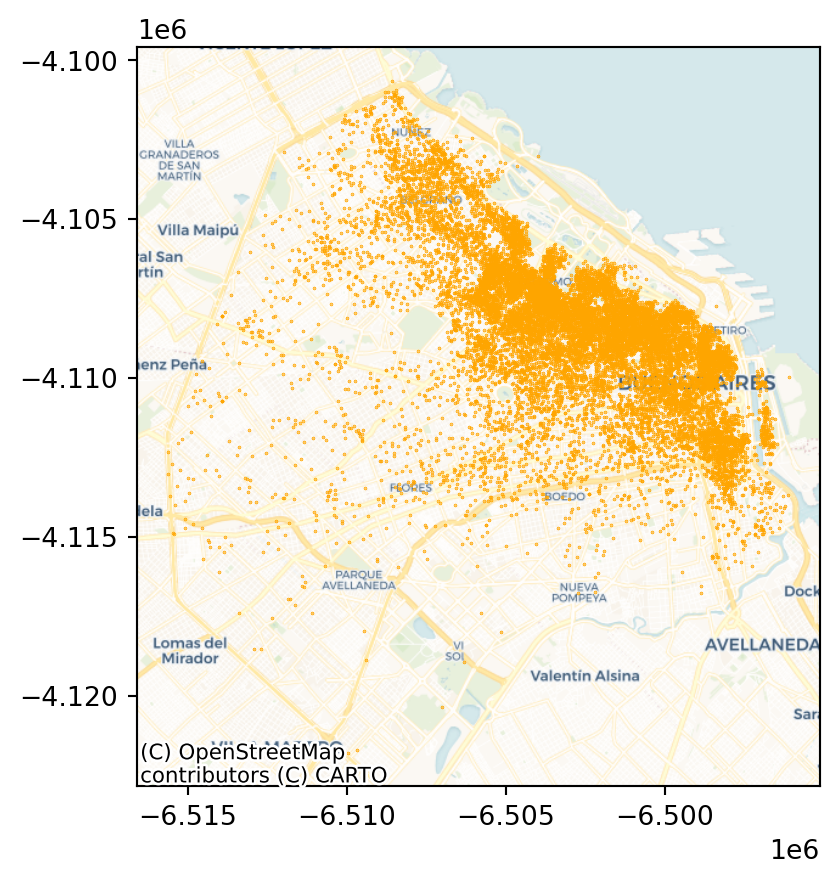

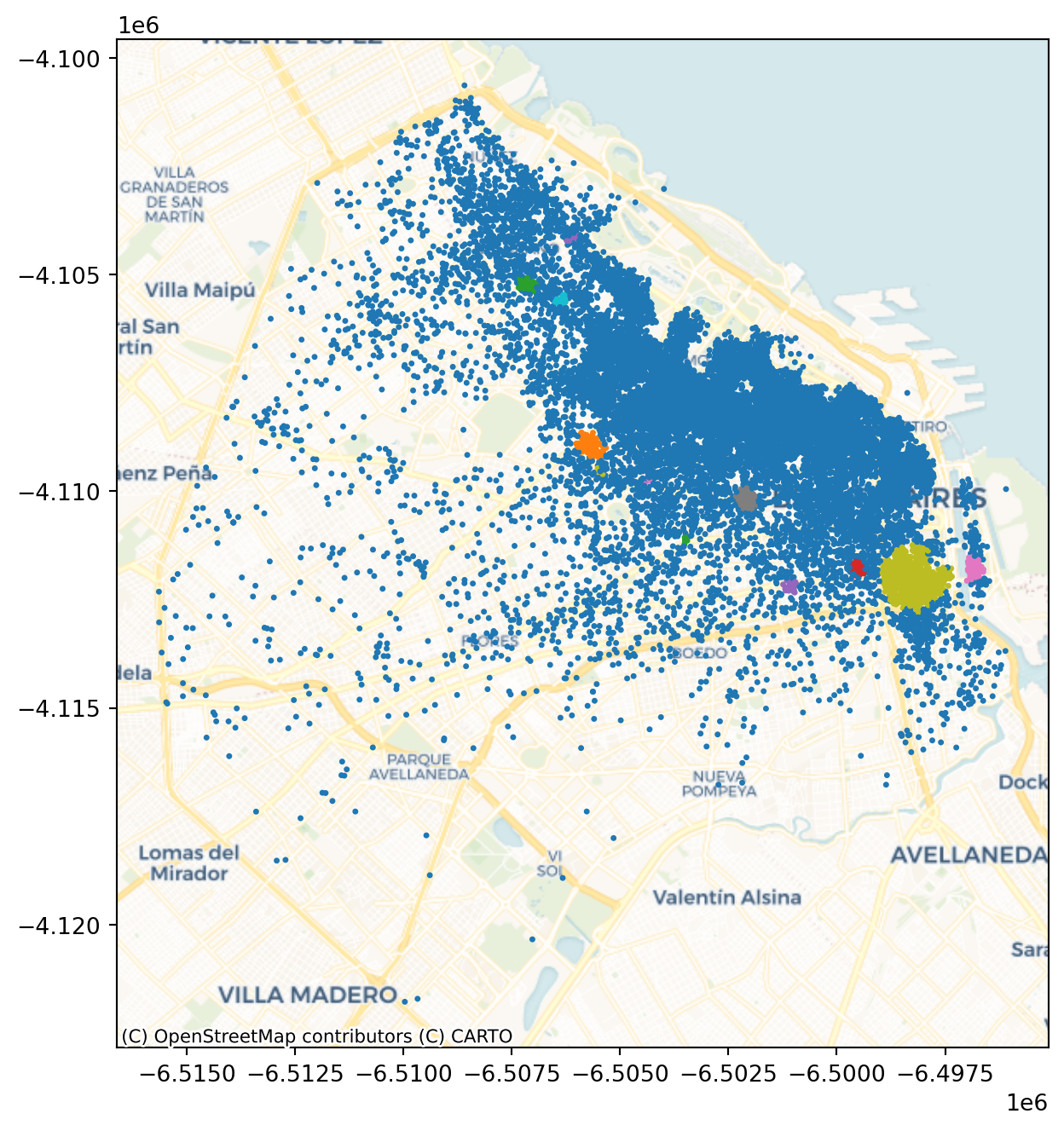

The A-DBSCAN algorithm

Once we know the parameters we’ll use, we can go ahead and run A-DBSCAN:

ax = listings_gdf_3857.plot(markersize=0.1, color='orange')

cx.add_basemap(ax, crs=listings_gdf_3857.crs.to_string(), source=cx.providers.CartoDB.Voyager);

plt.show()

Before we get going, we will also pull out the projected coordinates into separate columns:

listings_gdf_3857["X"] = listings_gdf_3857.geometry.x

listings_gdf_3857["Y"] = listings_gdf_3857.geometry.y# Get clusters

adbs = ADBSCAN(150, 20, pct_exact=0.5, reps=10, keep_solus=True)

np.random.seed(1234)

adbs.fit(listings_gdf_3857)ADBSCAN(eps=150, keep_solus=True, min_samples=20, pct_exact=0.5, reps=10)In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

ADBSCAN(eps=150, keep_solus=True, min_samples=20, pct_exact=0.5, reps=10)

ax = listings_gdf_3857.assign(lbls=adbs.votes["lbls"])\

.plot(column="lbls",

categorical=True,

markersize=2.5,

figsize=(8, 8)

)

cx.add_basemap(ax, crs= listings_gdf_3857.crs.to_string(), source=cx.providers.CartoDB.Voyager);

plt.show()

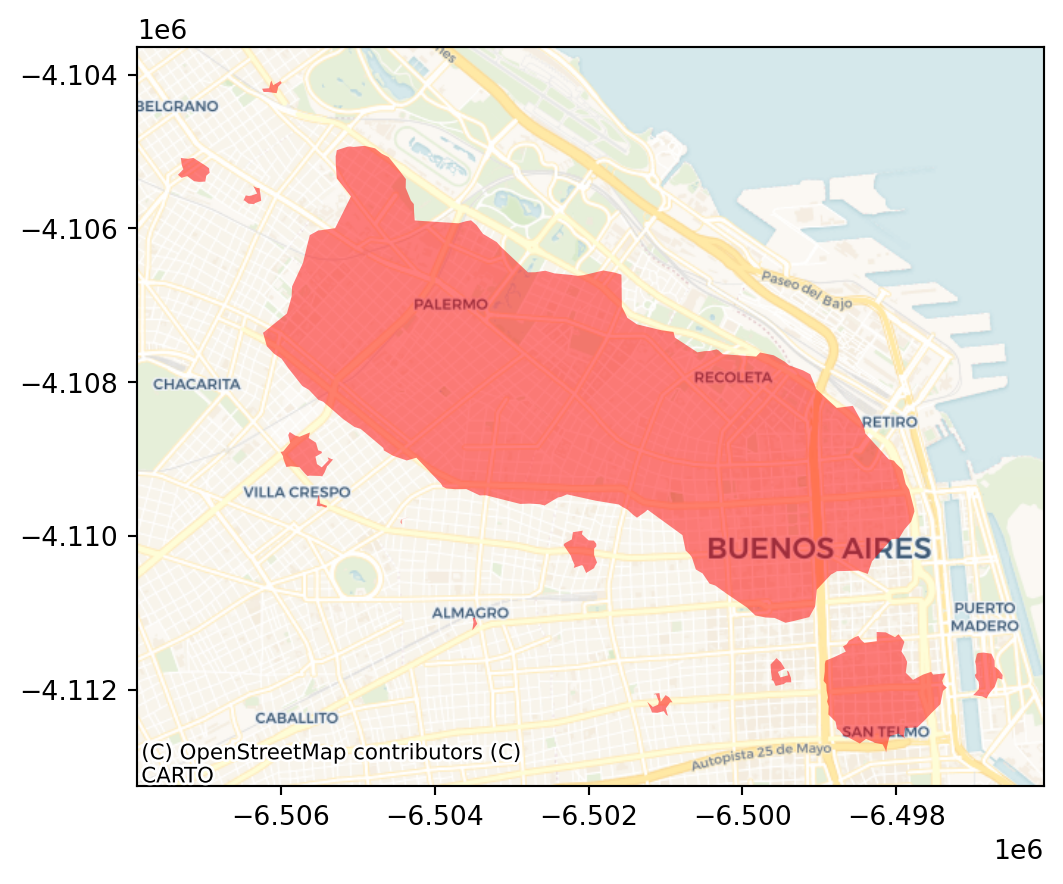

polys = get_cluster_boundary(adbs.votes["lbls"], listings_gdf_3857, crs=listings_gdf_3857.crs)ax = polys.plot(alpha=0.5, color="red")

cx.add_basemap(ax, crs=polys.crs.to_string(), source=cx.providers.CartoDB.Voyager);

plt.show()

The output is now very different, isn’t it? This exemplifies how different parameters can give rise to substantially different outcomes, even if the same data and algorithm are applied.